“Idleness is the enemy of the soul. Therefore, the community members should have specified periods for manual labor as well as for prayerful reading.”

RB 48.1

Welcome to my article unpacking verse 1 in Chapter 48 – The Daily Manual Labor (RB 48.1) from The Rule of St. Benedict. I learned a lot doing the research and hope that you find what I discovered interesting and helpful in your own view of work.

Before we begin our study, please read verses above slowly, noting any words or phrases that makes you either purr or hiss.

What do you think? When I first read the verse, my fur stood up at the opening sentence about idleness being an enemy of the soul. Humans can accuse us felines of having too much idleness. They mistake our frequent napping for sloth. But we nap to regain our energy and inspiration for meals, for more naps, for study, for our tasks, and for pouncing and prayer. It made me wonder how idleness could endanger my soul. Do you wonder this as well?

Let’s take a look at the monastic traditions about idleness and work inherited by Benedict.

Holy Scripture – Everyone is to Work

Br. Ricky suggested that I check out the book of Proverbs to begin my research. There are warnings about idleness that are downright unsettling. Here’s one.

“A little sleep, a little slumber,

a little folding of the hands to rest.”

Feline Cloister members

Srs. Nikki and Espy and Br. Ricky

zoned out.

“Go to the ant, you lazybones;

consider its ways, and be wise.

Without having any chief

or officer or ruler,

it prepares its food in summer,

and gathers its sustenance in harvest.

How long will you lie there, O lazybones?

When will you rise from your sleep?

A little sleep, a little slumber,

a little folding of the hands to rest,

and poverty will come upon you like a robber,

and want, like an armed warrior.”

Proverbs 6:9-11

In the New Testament we learn that Paul and the apostles were no lazybones. Paul was a real advocate of labor so that he would not be a burden to others.

“…work with your hands, as we directed you, so that you may behave properly toward outsiders and be dependent on no one.” 1 Thess. 4:11–12

“Thieves must give up stealing; rather let them labor and work honestly with their own hands, so as to have something to share with the needy.” Eph. 4:28

Early Monasticism – Work and Prayer Together

Following in the tradition of Paul and the apostles, the desert mothers and fathers worked to support themselves. These early ardent Christinas did simple, repetitive manual labor like making reed baskets.

They would meditate on and recite Scripture while they worked, thus keeping at bay any wiles of the Evil One or of their own weaknesses.

A hermitage in the desert near Naqlun, Fayyoum.

Courtesy of Karel Innemée.

Pachomius looking worried. He had a big job

to figure out how the work was to be organized.

Pachomius – Work to Support the Community

I discovered a monk named Pachomius, 290-346 CE, who is considered the founder of cenobitic life favored by Benedict (RB 1.13). (See “Cenobite” in the Glossary.)

Pachomius wrote the first known monastic rule for the vast community that he founded. This confederation of nine monasteries for men and two for women together numbered over five thousand people. [1] Wow!! What does Pachomius say about work and idleness in his rule?

There is an excellent book about early monastic rules by feline scholar Br. Terrence Sebastian Furlong, OSB-F, PhD-F. Furlong pawed that work

“was necessary because for [Pachomian communities] work was not so much an ascetical exercise as a practical necessity to support a vast community.” [2]

That’s a good reason to work I will share with Amma so that we don’t run out of cat treats!

Basil of Caesarea– Balancing Work and Prayer

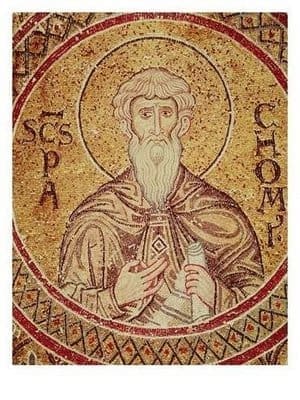

Basil of Caesarea, (330-379 CE), established two monastic communities and became the bishop of Caesarea, located on the coastal plain of present-day Israel.

One of the points of contention in the church of Cappadocia was tension between work and prayer. What did the biblical command to “pray always (1 Thes 5:17) look like? Would you pray and not work?

Basil countered this by saying “one must work and work diligently…piety [is not] an excuse for idleness or a means of avoiding toil.” In the last chapters of his Long Rules, we see that work is important because it produces results “whether income or other products, that enable us to care for the needy.” [3]

Because the wealthy shunned work, to help these monastics reframe their views Basil cited that work benefits the body. Work also focuses the mind to promote recollection of God and to make prayer easier. Basil also encouraged members to achieve a healthy balance of prayer and work. Basil “probably just saw it as a good way to keep the spiritual life anchored in the real world, and…in solidarity with the rest of the world.” [4]

Benedict would not have read Pachomius’ Rule because it was written in Coptic and Benedict read in Latin. But Benedict read and admired Basil of Caesarea (330-379) and names Basil’s rules as important reading in his own Rule (RB 73.5)

How Caesarea may have looked in the fourth century

Augustine of Hippo – Work as a Natural Aspect of Being Human

The monastic rule of Augustine of Hippo (354-430 CE) influenced Benedict greatly. Augustine became one of the great theologians of Western Christianity. As Bishop of Hippo he turned “his own household of clerics into a quasi-monastery, with a common life and common ownership of property, which, one might guess, was not received warmly by all clergy.” [5]

Augustine’s reflections on monastic labor serve as the primary reference point for handbooks on monastic labor in the Western tradition. Augustine maintains that there was work in paradise before the fall into sin. Consequently, work is a natural aspect of human life. Monks serve as an exemplar of charitable simplicity sustained by labor. Labor enables self-sufficiency and is guided by love towards acts of charity. All who are able ought to work so that charitable provision might be made out of the ensuing abundance. [6]

Three early churches found in Egypt’s Western desert date to the fourth to seventh centuries A.D. (Image credit: Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities)

John Cassian: Work in Egyptian Monasticism

Monk and theologian John Cassian (360-435 CE) documented the monastic tradition of Egypt in the early part of the fifth century. His writing had a deep and profound influence on Benedict. In the last chapter of his Rule Benedict states that the writings of Cassian are “must” readings. (RB 73.5)

In his Institutes Cassian documents the alternation between the daily offices of communal prayer and manual labor. For the Egyptian monk, manual labor was steeped in the recitation of Holy Scripture. I asked Novice Sabastian Thomas to help me find an illustrative quote. Here’s what he found.

The daily offices were celebrated “continuously and spontaneously throughout the course of the whole day in tandem with their work.” [7]

“For they are constantly doing manual labor alone in their cells in such a way that they almost never omit meditating on the psalms and on other parts of Scripture…” Cassian noted that the offices and other spiritual responsibilities are done in a way that “the necessary duties of work may never be impeded.” [8]

Novice Sebastian Thomas

Novice Scholar Little Jenny studying Benedictine scholar Albert de Vogue’s book, A Critical Study of the Rule of St. Benedict, Vol. 1

The Rule of the Master – Work to Avoid Sin

Novice Litle Jenny, our resident novice scholar, suggested that I check out the Rule of the Master, Benedict’s main written resource from which he drew extensive text. This rule is thought to have been written in the sixth century by an unknown abbot. Benedict drew extensive text from this earlier rule, although not everything, thank heaven!

In Chapter 50 the Master detailed the daily labor in 75 verses. What makes my fur stand on end is his insistence that idleness is the enemy of the soul. Take a listen…

“After the Divine Office has ceased during the day, we do not want these intervals when the psalmody of the Hours is suspended to be spent idly lest short-termed idleness produce no long-term profit, because an idle man produces death and is always craving something.” [9]

“…while a brother is engaged in some task he fixes his eyes on his work and thereby occupies his attention with what he is doing and has no time to think about anything else, and is not submerged in a flood of desires.” [10]

Br. Terrence Furlong counted eight repetitions of the phrase “As soon as they come out…” the members are to immediately return to their work or other activity. Because the human soul, in the Master’s view, is under constant pressure from both the flesh and the spirit, activity must take the place of idleness and idle thought. “The unoccupied soul will be invaded by evil influences, so it must be engaged in holy thoughts and activities.” [11] I’m sure fglad that the Feline Cloister follows The RUle of St. Benedict and no the Rule of the Master!

Anglican Benedictine nuns at Malling Abbey in England

working at ”what needs to be done:” (RB 48. 3, 6)

Clearing the stream.

The Rule of St. Benedict – Work is Doing What Needs to be Done Within a Balanced Life

Novice Little Jenny explained that while Benedict took text and ideas from the Rule of the Master, he made big changes, too. In the chapter on daily manual labor he reduces the number of verses from 78 to 20.

A big difference in these two rules is that Benedict removes the repeated insistence found in the Master’s rule that work is done to avoid sin. I don’t believe that he wasn’t concerned about idleness within his community. He just put the focus elsewhere.

For Benedict work was primarily utilitarian. The monastics are to do “whatever work needs to be done.” (RB 48.6, 9) They are to work at their “assigned tasks.” (RB 48.11,14,22) He wanted everyone to contribute, too, so that love within the community would be mutual. (See RB 35 – Kitchen Servers of the Week as an example of this.) I like that he doesn’t clutter the chapter with meticulous detail about who does what when as the Master does.

After mentioning that idleness is the enemy of the soul, he simply instructs that the day be divided into “specified periods for manual labor as well as for prayerful reading.” An important teaching in the Rule is this idea of balance, something many humans get out of whack. Less so with us felines. Benedict suggests that we balance work, the daily office and prayer.

It seems to me that Benedict thought a good deal more of the monastic’s ability to stay focused on his or her journey to God and on the work that must be done without a lot of “outside help.”

Closing Thoughts

Well, that is more than I planned on mewing, but I found it all very interesting and hope you did too.

Do you think that idleness is the enemy of the soul? There is some truth in that. When I am idle, just hanging around, my wandering mind turns to an obsession over crunchy cat treats. Or I take to devising how I can “reform” some of my confreres. Not good! Thoughts like these really separate me from God.

After all that I have read, my belief is that as Christ’s hands, feet and heart, we have a holy responsibility to do the work that God calls us to. We simply must share our God-given gifts and skills for the betterment of our communities and, really, the world. Not doing this, our lives and our souls will shrivel and close in on ourselves. Not good.

I for one don’t want to be a feline who lies on the couch watching soaps and eating crunchy cat treats. How about you?

Novice Miss Sassafras tuckered out after doing a good job

Take care now and God bless you and your work.

Your feline friend,

Novice Miss Sassafras

Br. Benedict Basil, OSB-F

succumbing to a stupor of idleness

© March 2023 Jane Tomaine & Novice Miss Sassafras

Endnotes

[1] Derwas J. Chitty, The Desert a City: An Introduction to the Study of Egyptian and Palestinian Monasticism under the Christian Empire (Crestwood, NY: St. Valdimer’s Seminary Press, 1999), 24.

[2] Here Br. Furlong quotes, Terrence Kardong, Pillars of Community: Four Rules of Pre-Benedictine Monastic Life (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 2010), 97.

[3] Ibid., 58

[4] Ibid, 57-59.

[5] Jane Tomaine, The Rule of Benedict: Christian Monastic Wisdom for Daily Living (Nashville, TN: SkyLight Paths Publishing, 2016), xx.

[6] Jeremy Kidwell, “Labour in St. Augustine” https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jeremy-Kidwell/publication/257997984_Labour_in_St_Augustine/links/55c88a1e08aeb975674740b3/Labour-in-St-Augustine.pdf?origin=publication_detail, 779-780.

[7] John Cassian, The Institutes, trans. Boniface Ramsey (Mahwah, NJ: Newman Press of the Paulist Press, 2000), Book 3: Chapter 2, p. 59.

[8] Loc.cit.

[9] The Rule of the Master, trans Luke Eberle (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1977), Chapter 50, Verse 2 [RM 50.2], p. 208-209.

[10] Ibid., RM 50.3-4.

[11] Terrence G. Kardong, Benedict’s Rule: A Translation and Commentary (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1996), 396-397.