Who Is St. Benedict?

Hello and welcome! In this section of the website Jane Tomaine, author of St. Benedict’s Toolbox and abbess of the Feline Cloister, will introduce you to St. Benedict, a monastic abbot who lived in the sixth century. Abbot Benedict wrote what he called a “a little rule” for the members of his monastery to help them follow Christ and to live well together in community. Today many of us find that this little Rule helps us to do the same.

Who was this man whose monastic Rule became standard for monasteries by the early Middle Ages? What was his life like? What kind of a person was he? How did we come to know about him? Did he perform miracles like so many of the saints?

Amma Jane will be exploring these questions through an interview with a famous man of the sixth century. This man was inspired to write about the life of St Benedict not all that long after Benedict’s death in 547 CE. How can I interview this biographer of St. Benedict, who himself died in 604 CE? Easy. Read on…

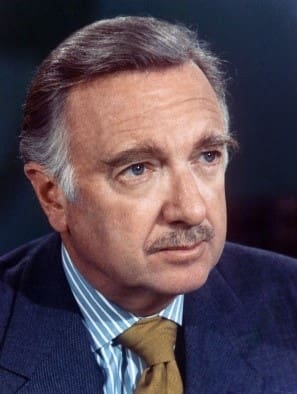

Walter Cronkite

Introduction to the Format of this Section

In the 1950’s Walter Cronkite, an American broadcaster, had a television show entitled “You Are There”. Viewers learned about people and history through interviews with actors and actresses portraying people such as Socrates, Benjamin Franklin, Clara Barton, and others. Wanting to have some fun with what could be a dry recitation of information, I (Jane) decided to borrow Walter Cronkite’s format to tell you about St. Benedict, the abbot, who lived from 480 – 547 CE.

The noted individual I will be interviewing in this 21st century rendition of “You Are There” is Pope Gregory 1 (540 – 604). Pope Gregory, also called Saint Gregory the Great , was Bishop of Rome from 594 to his death. We will learn about Benedict through my conversation with this venerable pope who wrote about St. Benedict.

If you are viewing this page with others, feel free to have three people take the three parts – announcer/reader of text in parentheses and/or italics, Jane and Pope Gregory. Whether you are viewing the interview alone or with others, the only thing you need to bring is your imagination. I hope you find the interview interesting and engaging.

NOTE: All quotations from Pope Gregory’s Dialogues are found in Early Christian Lives, trans and edited by Carolinne Ware (London: Penguin Books, 1998) unless otherwise noted. Specific page numbers appear in the endnotes.

(The voice of an announcer opens the interview.)

“June 25, 596

Rome, Italy

You Are There!“

Jane (J): Hello and welcome, listeners and readers. We are about to meet the current Pope, Pope Gregory I, who lived from 540 – 604. Pope Gregory will speak with us about St. Benedict, the abbot of Monte Cassino in Italy, who wrote a Rule of Life for members of his community. Let’s go to sixth century Rome now!

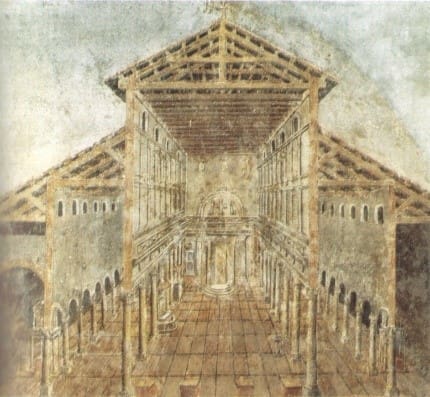

The camera opens with a view of the outside of the sixth century St. Peter’s. After pausing to look at the structure, we move inside the church.

The building is much humbler that the basilica of today, having a central aisle with two side aisles. We walk down one of the side aisles to the front of the church and exit at a side door.

Before us is a large stone dwelling, the Pope’s home. With sweeping arm gesture and smile, an attendant invites us inside. Walking under the door’s rounded arch and into the main room, we see in the dim light a wooden desk, a candle and the Pope bent over his work.

The camera moves in on this distinguished looking man.

St. Benedict and the Dialogues of Pope Gregory the Great

He is a kind-looking man, whose spirituality and approach to life was formed by years of contemplative living in a monastic community, a community he was reluctant to leave for the public life and pressures of the papacy.

Jane (J):.) Hello, Pope Gregory. Thank you for taking the time to meet with us.

Pope Gregory I (G): (The Pope looks up from his writing desk, turns toward the camera, smiles, and sets his quill pen down on the desk.) Greetings and welcome to you and your readers and listeners. I am always as happy to speak about Abbot Benedict as I was to write about him.

J: And as we are to listen to you, Pope Gregory. St. Benedict’s life is the second book of your work entitled Dialogues, which I understand are four books recounting miracles by holy people in Italy. How did you come to write about Abbot Benedict?

G: Some friends asked me to write about him. As I recall, it was 593 or 594 when I penned it all.

J: The biography is in the format of what we now call a hagiography. A hagiography is a kind of biography which expresses deep reverence and respect for the subject individual. This form was often used to detail accounts of miracles performed by saints. An important goal is to inspire readers and show them how much God is involved in our lives.

G: Correct. When times are difficult, like right now with civic affairs in turmoil, we all need assurance. My respect for Abbot Benedict, the man of God, knows no bounds. I began the second book of the Dialogues, the book about Abbot Benedict, with these words.

“There was a man whose life was worthy of veneration, Benedict by name and blessed by grace.” [1]

J: You didn’t know St. Benedict personally. How did you learn about him?

G: Checking sources, right? (Gregory says with a twinkle in his eye.) That must be important in your time. “I learned from the account of four of his disciples, namely Constantine, an extremely respectable man who succeeded Benedict as the head of the monastery in Monte Cassino.” I can talk more about Monte Cassino later. I also learned about Benedict from “Valentinian who was for many years in charge of the Lateran monastery; Simplicius, who was the third person to rule his community after him; and Honoratus who is still in charge now of the cell in which Benedict first lived.” [2] This was at Subiaco, where Benedict had established 12 monasteries.

San Benedetto Church in Norcia – Destroyed in Earthquake October 30, 2016

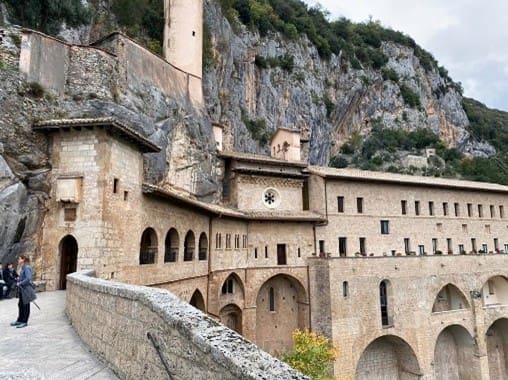

Monastery of San Benedetto Subiaco on the site where Benedict was a hermit

Benedict’s Quest for a Holy Life and Dangers Encountered

J: When was Benedict born?

G: We believe that Benedict was born around the year 480 in the Umbrian province of Nursia in Italy after the fall of Rome in A.D. 410 and the official end of the Western empire in 476. It was a dangerous and turbulent time, not unlike the time I now live in. I have been told that Benedict’s family was one of high station.

J: Did Benedict receive an education?

G: Yes, but that was not what he wanted. He was sent to Rome for a liberal education, “but when he noticed that many students fell headlong into vice, he stepped back, as it were, just as he was about to enter the world, fearing that if any worldly knowledge should touch him, he, too, would then fall, body and soul, into the bottomless abyss.” He left everything – home, property, and “wishing to please God alone, he went in search of the habit of a holy way of life.” [3]

J: Where did Benedict go in search of this holy way of life?

G: He first went to a town called Effide. After performing a miracle there and receiving too much attention, he left.. This man of humility desired more to work hard on God’s behalf than to be “exalted by the acclaim in this life.” [4]

He then ventured to an area near the town of Subiaco. Here he lived as a hermit in a hillside cave for three years. While there he was “discovered” by others who recognized his holiness and wisdom. As I mentioned before, Honoratus is still there.

“As word of his exemplary life spread, his name became increasingly famous.” [5]

J: Wasn’t St. Benedict asked to be the abbot at an existing monastery in Subiaco? How did that go?

G: Yes, to your first question, and not well, to your second. After that community had literally begged him to become their abbot, they regretted their eagerness.

J: Why was that?

G: Everyone seems to want an easy life, right, and to do what they want to do whenever it suits them. Benedict asked the community to live by a rule that had a greater strictness from what they had been following. As I wrote in the Dialogues, “unlawful things were no longer lawful, and they were aggrieved at having to abandon their habits.” To solve this problem, the community decided to rid themselves of this man who was cramping their style of life. So, one day they poisoned his wine. But when he blessed that tainted cup, it shattered. [6]

J: Great story! Did Benedict leave that monastery?

G: Absolutely. He knew that if he had stayed in a place with so much resistance and so many unholy habits his search for God would have been jeopardy. As I wrote, “he might perhaps have exceeded his strength and lost his peace and turned his mind’s eye away from the light of contemplation.” [7] Plus, he wanted to help people find Christ who were willing to be led.

J: What did St. Benedict do then?

G: He established a new monastery in Subiaco. I’m curious. Does it still exist in your time? (Jane nods yes) Good. Benedict also formed eleven other monasteries on a hillside in that area.

J: Was Benedict accepted by the Church and the people in that area?

G: Mixed acceptance. Because of Benedict, “The people of this area for miles around were now fervent in their love of the Lord God, Jesus Christ…but wicked men have a tendency to be jealous of others’ virtue which they cannot be bothered to strive for themselves.”

The priest of a neighboring church, Florentius, was envious of Benedict and “the flames of jealousy burned all the more within him.” He gave Benedict bread laced with poison. [8] I’d like to read this great story to you and your viewers. The poison hidden in the bread was not hidden from Benedict.

J: Oh, no! What happened? Please read!

G: (Reading from Dialogues, the Pope continues.)

“At mealtimes a raven used to come out of the nearby wood and take bread from Benedict’s had. This time, when it came as usual, the man of God threw down in front of the raven the bread that the priest had handed him, saying, ‘In the name of the Lord Jesus take this bread and drop it somewhere where no one can find it.” The raven was afraid to take the bread, but Benedict reassured him, “Pick it up, pick it up. Do not be afraid. Just drop it where it cannot be found.” And so the raven did as Benedict asked, and came back, safe and sound. [9]

J: I’ll bet Benedict was really angry at this priest.

G: On the contrary, he grieved for the priest more than for himself. Later, Florentius was killed in the collapse of his house.

J: Benedict certainly must have been delighted with this development!

G: No, he sobbed with grief, either for Florentius or that some of the brothers cheered at the priest’s demise.

J: What charity he had as well as concern for his brothers! But I know that St. Benedict left that area.

G: Yes, he did, going to a fortification known as Casinum and established the monastery of Monte Cassino which remains to this day. It was there that he wrote his Rule and performed many miracles in that place.

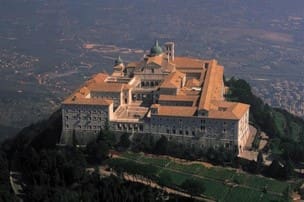

St. Benedict at Monte Cassino

J: Did St. Benedict move again or did he stay at Monte Cassino?

G: Abbot Benedict spent the rest of his life at Monte Cassino, which, of course, is where he wrote his Rule. I was born seven years before this man of God died. He died on March 21, 547.

J: And I must mention that is the same day in March as birth of the 18th century Baroque composer, Johann Sebastian Bach! Where is Benedict buried?

G: At Monte Cassino, at least some believe so. The sad truth is that forty years after his death in 587, Monte Cassino was destroyed by invading Lombards, which was a vision that Benedict saw before he died. The monastery was rebuilt.

J: (I need to make a judgement call about what to share with the Pope about the monastery building. Yes, the monastery was rebuilt, but destroyed twice more, the final time during World War II. An imposing structure was rebuilt, and the monastery today is a functioning Benedictine monastery. A debate continues over where St. Benedict’s remains are enshrined. This honor is also claimed by the Abbey of St. Benoit-sur-Loire in France, who state that St. Benedict’s remains were brought there in the 7th century. I choose not to share all this with Pope Gregory.)

Above is the Reliquary for St Benedict and Scholastica at Monte Cassino

At right is pictured the Reliquary for St. Benedict at Fleury Abbey

St. Benedict and St. Scholastica

J: Did St. Benedict have any siblings? Did he have a sister or a brother?

G: Yes. “His sister, whose name was Scholastica, had been dedicated to the almighty Lord since her very infancy. She used to come to see Benedict once a year and the man of God would come down to meet her at a property belonging to the monastery not far from the gate.” [10]

J: Sounds like women weren’t allowed in the monasteries at this time.

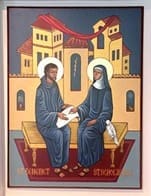

Icon written by Sister Paula Howard

G: Exactly. During one visit, Benedict and Scholastica “spent the whole day praising God and in holy conversation, and when night’s darkness fell, they ate a meal together. While they were seated at table, talking of holy matters, it began to get rather late and so this nun, Benedict’s sister, made the following request, ‘I beg you not to leave me tonight, so that we might talk until morning about the joys of heavenly life.’ Benedict answered her, ‘What are you saying sister? I certainly cannot stay away from my monastery.’”

Undeterred and in great faith in God, Scholastica “put her hands together on the table and bent her head in her hands to pray to the almighty Lord. When she lifted her head from the table, such violent lightening and thunder burst forth, together with a great downpour of rain, that neither the venerable Benedict nor the brothers who were with him could set foot outside the door of the place where they were sitting.”

J: I would guess that Benedict was not thrilled about this turn of events.

G: True, but because he couldn’t leave they spent the whole night in “holy conversation about the spiritual life.” [11]

J: What a great story!

G: (The Pope smiles.) And there are many other wonderful stories in my book about Benedict.

Canterbury Cathedral Today

When and Why was St. Benedict Made a Saint?

G: And now I have a question for you! Quite a number of times you have referred to Abbot Benedict as St. Benedict? When did Benedict become a saint?

J: It was in 1220.

G: Whoa! That is a LONG way off. May I be so bold to ask, given it took so long for this to happen and why Benedict was finally made a saint?

J: Well, I will share what I know and it began with you!

G: Me? Because I sent Augustine to England last year (595 C.E.), carrying with him the traditions of St. Benedict?

J: I believe so. You started the tremendous influence Benedict was to have on monasticism, the Church and what was to become Europe. Augustine of Canterbury ultimately became the first Archbishop of Canterbury. Monasteries all over England became Benedictine.

Later, in the eighth century a monk named Benedict of Aniane (750-821 CE) adopted Benedict’s Rule for his monastery. He did this to reform monasticism which, at that time, had slid into a worldly mode, like those monks that tried to poison Benedict. By the early 9th century, Benedict’s Rule was obligatory for all the monks in the empire headed by an emperor named Charlemagne.

G: That is fantastic. I am thrilled to learn this.

J: I agree. Benedict became the patriarch of Western monasticism and his Rule the most influential in the Western Church. Many believe that the Rule and the Benedictine monasteries saved Europe from ruin. Esther de Waal, a noted author about the Rule in my time, wrote that “monasteries came to stand out as centres of light and learning.” [12]

What Kind of Person was St. Benedict?

J: What wonderful stories and information you have shared with us, Pope Gregory. Is there anything else you wish to tell us about Benedict? What else do we need to know about St. Benedict? And how can we learn more about who he was like as a person?

G: May I read from Dialogues?

J: Oh, yes!

G: (The Pope clears his throat and begins to read.)

“I do not wish you to be unaware that amidst all the miracles which made him famous throughout the world the man of God was no less outstanding for the wisdom of his teaching. For he wrote a Rule for the brothers which is remarkable for its discretion and the clarity of its language. If anyone should wish to know about his character or his way of life in greater detail, he [or she] can discover in the teaching of that Rule a complete account of Benedict’s practice for the holy man was incapable of teaching anything that was contrary to the way he lived.” [13]

J: AMEN to that, Pope Gregory! I want to encourage our readers and listeners to find a copy of your second book of Dialogues and read all the tremendous miracles performed by this man of God, St. Benedict. It is an interesting and inspiring read.

G: (Pope Gregory smiles) It was a joy and honor to write about such a holy man of God, and especially now that I know the breadth of his influence.

J: Thank you so much for sharing about St. Benedict. We deeply appreciate the time you took for us.

G: A pleasure. God bless you and your readers and listeners. (The Pope smiles, turns to his desk, picks up his quill pen, and resumes writing.)

(The voice of the announcer)

“What sort of day was it? A day like all days, filled with those events and people that alter and illuminate our times.”

And you were there!

Endnotes

1-3 Carolinne Ware, Early Christian Lives, (London: Penguin Books, 1998), 165.

4 Ware, 166

5 Ware, 169

6-7 Ware 170

8-9 Ware, 176

10-11 Ware, 178, 179

12 Esther de Waal, Seeking God: The Way of St. Benedict (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1984, 2001), 20.

13 Ware, 200.

To read the Dialogues on the Order of St. Benedict Website, click here.